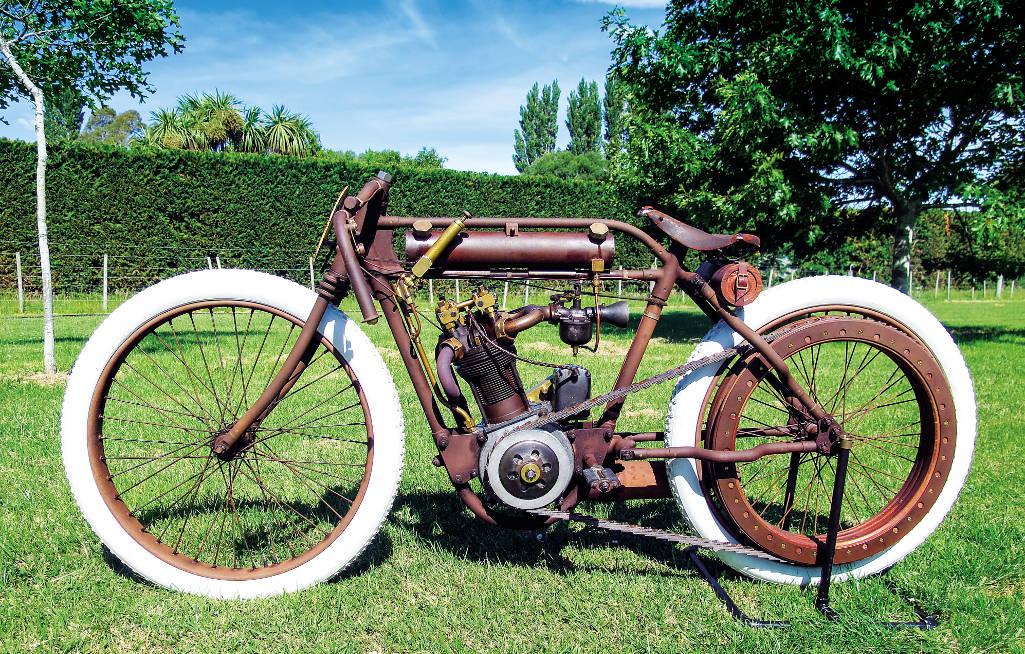

It may look like a 100-year old barn find, but Chris Gordon’s Board-Tracker was crafted right here in NZ in the 21st Century.

Words and pics: Dave Britten

Chris Gordon is a motorcycle enthusiast, but not a conventional one, rather than riding bikes his preference is in their creation. His latest project was inspired by a friend’s idea to build a Norton-engined board-tracker and Chris thought that something similar to an early 20th Century Indian V-twin might interesting.

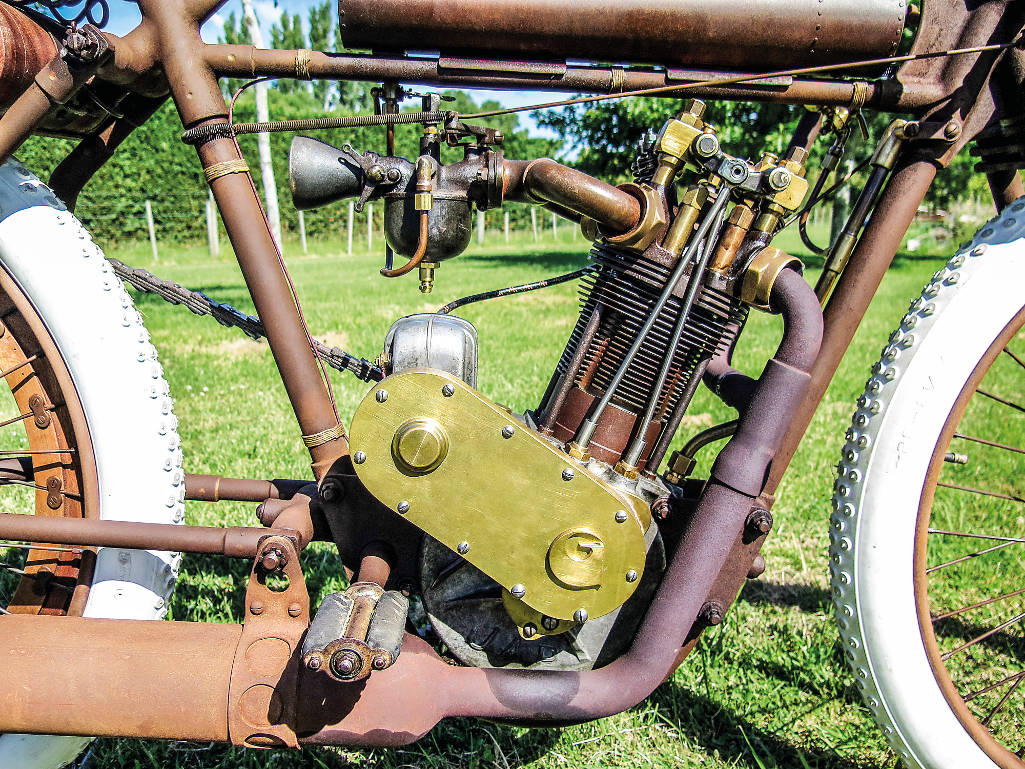

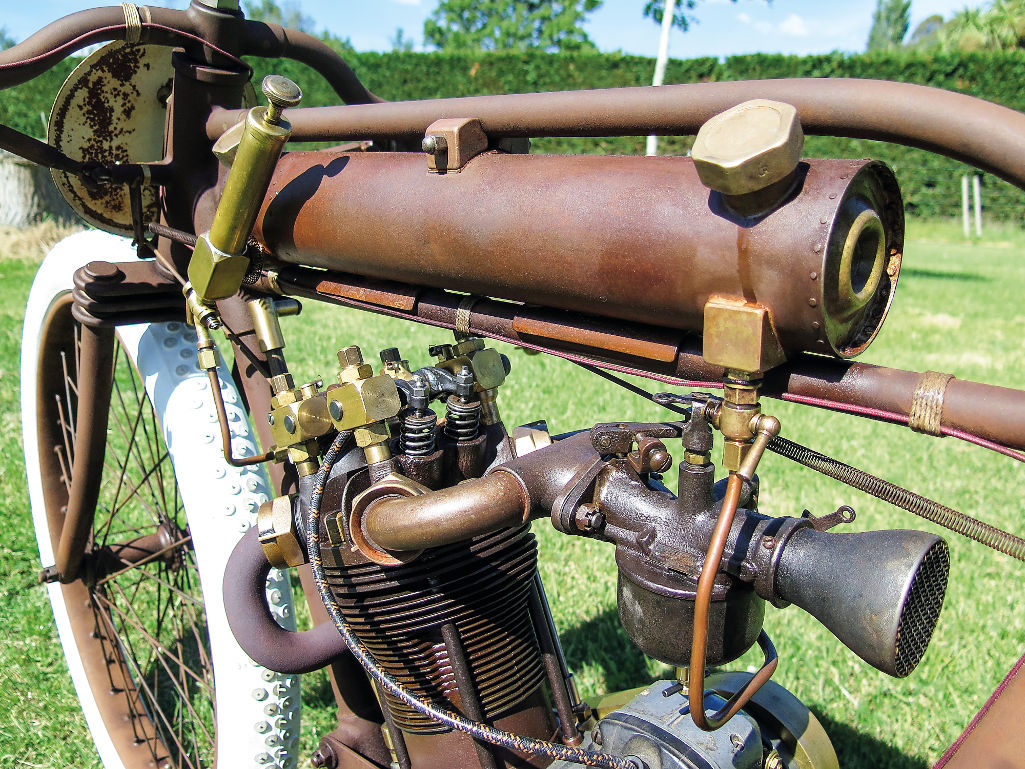

Thus, in March 2015 he started drawing a 1000cc 40-degree engine. Chris decided that he would incorporate certain technical improvements that a clever engineer might have included in 1910, so a four-valve head was always going to be part of the design. By making the head in an X shape, with four individual intake and exhaust ports, the head would be reversible and so useable on both the front and rear cylinders, with the carburettor in the usual position between the cylinders.

Thus, in March 2015 he started drawing a 1000cc 40-degree engine. Chris decided that he would incorporate certain technical improvements that a clever engineer might have included in 1910, so a four-valve head was always going to be part of the design. By making the head in an X shape, with four individual intake and exhaust ports, the head would be reversible and so useable on both the front and rear cylinders, with the carburettor in the usual position between the cylinders.

Honda makes a 250cc scooter with a two-valve head and two each of those valves were chosen, but due to the low upper rev limit expected for the board-tracker, only one spring was needed for each.

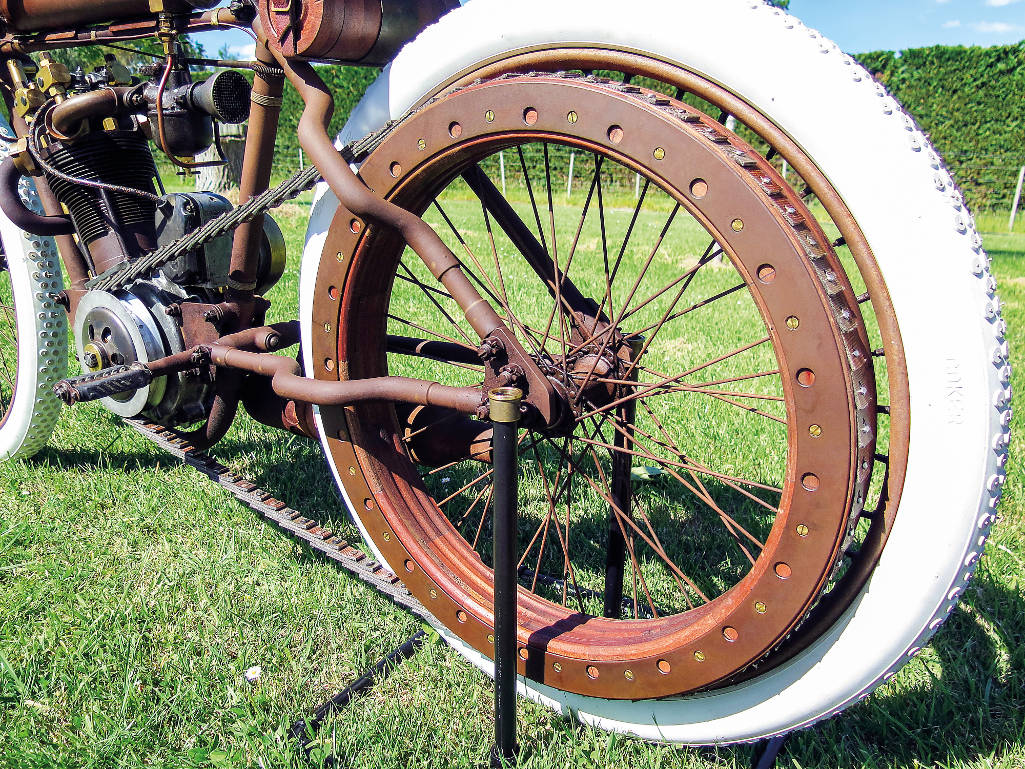

It was of utmost importance that the bike look right and this completely depends on the wheels – old-fashioned they might be, but 28 x 2.5-inch rims and matching tyres were essential. In New Zealand, Chris could only find 28 x 3-inch rims, and although the difference is small, it is important, so considerable effort was spent in searching the world for the correct sized parts. A set of clincher rims and Coker button tyres was eventually found in the USA. Chris made his own hubs and had them laced to new spokes.

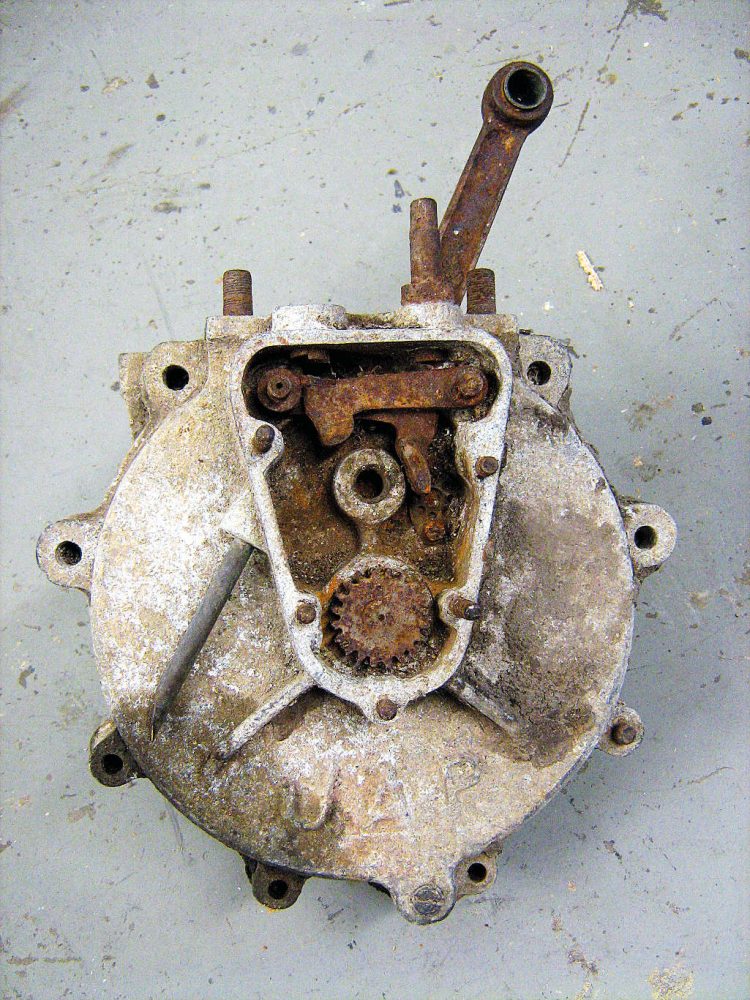

In May 2015, Chris bought a JAP crankcase, complete with crankshaft, at an Ashburton swap meet. It appeared in poor condition and having been open to the elements for literally decades, was seized solid, but after persevering in its dismantling by repeatedly heating and cooling it in a drum of diesel for several weeks, it was persuaded to come apart without any further damage being inflicted. The serial number put its manufacture at 1908, so Chris took this as a sign that he should abandon the earlier V-twin idea and instead make a single-cylinder machine.

In May 2015, Chris bought a JAP crankcase, complete with crankshaft, at an Ashburton swap meet. It appeared in poor condition and having been open to the elements for literally decades, was seized solid, but after persevering in its dismantling by repeatedly heating and cooling it in a drum of diesel for several weeks, it was persuaded to come apart without any further damage being inflicted. The serial number put its manufacture at 1908, so Chris took this as a sign that he should abandon the earlier V-twin idea and instead make a single-cylinder machine.

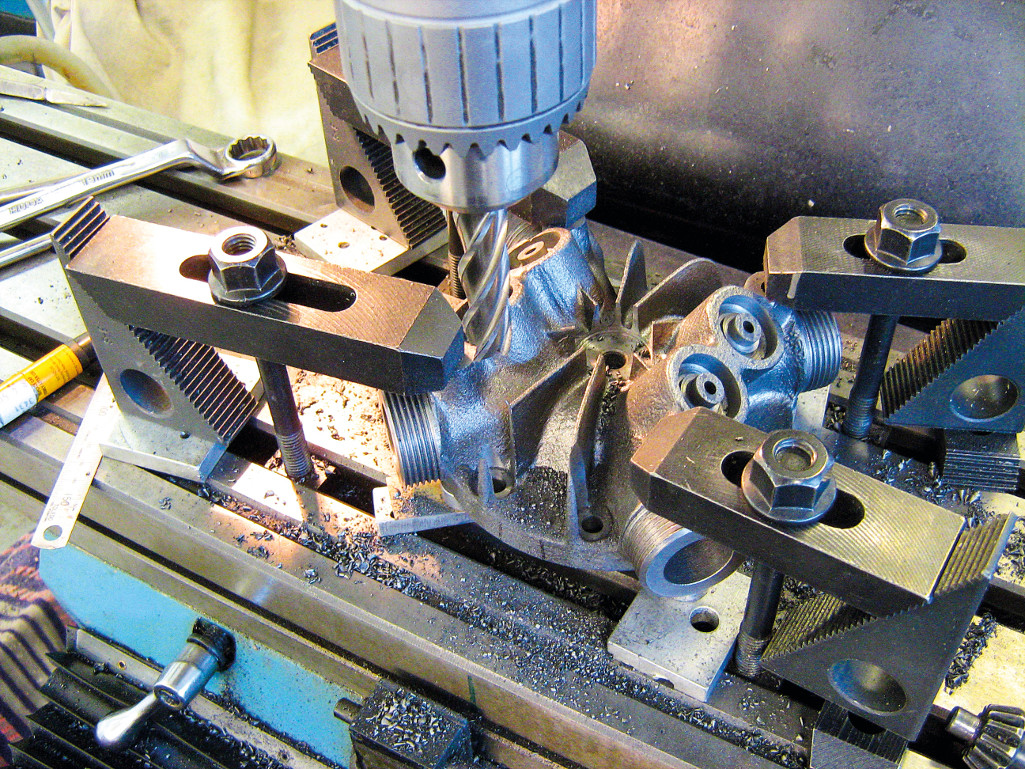

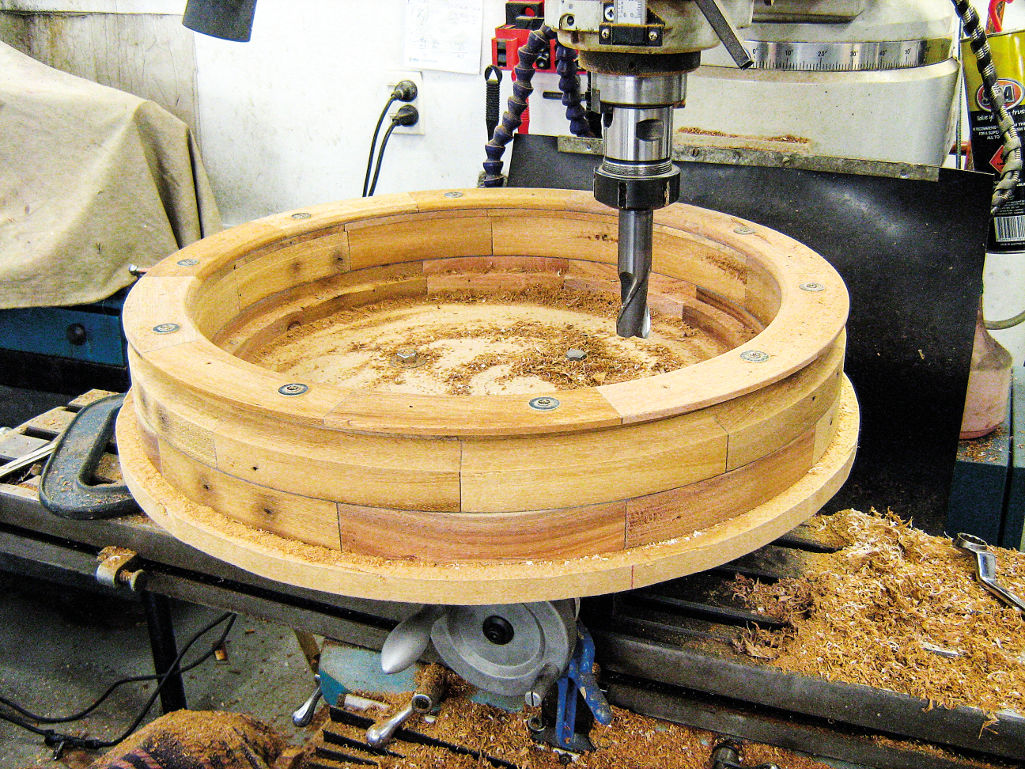

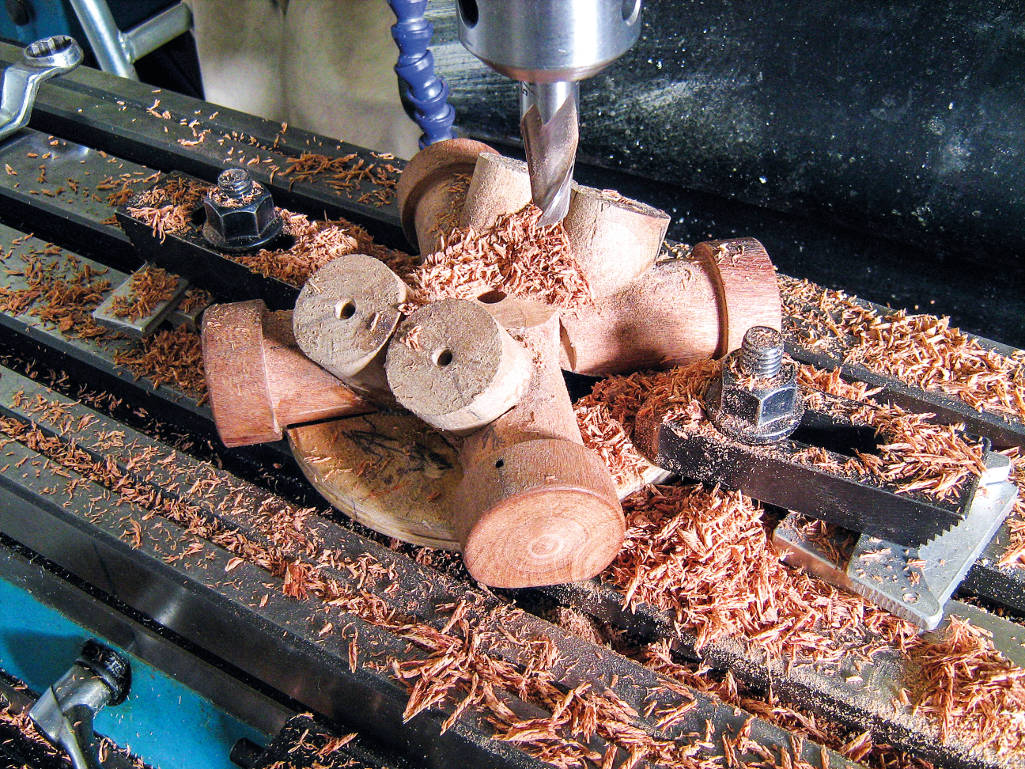

At this time, the wooden pattern for the cylinder head and flywheels were completed, and Chris had blanks of these parts cast in iron at Cancast in Washdyke. Making the wooden pattern for the sand-casting was particularly tricky, due to the number of undercuts needed, and this prevented the head from being extracted easily from the mould, but by making the core in several pieces, the result was a success.

Other internal parts for the engine were made or adapted from the Honda CF250 scooter’s design, and the final camshaft, gear driven directly off the crankshaft has just one lobe, with the four overhead valves operated by long pushrods. All bearings were changed from originally being bronze bushes to needle-rollers, although the original total-loss oiling system remains, and is effective, given the modest power and relatively low rpm used.

Other internal parts for the engine were made or adapted from the Honda CF250 scooter’s design, and the final camshaft, gear driven directly off the crankshaft has just one lobe, with the four overhead valves operated by long pushrods. All bearings were changed from originally being bronze bushes to needle-rollers, although the original total-loss oiling system remains, and is effective, given the modest power and relatively low rpm used.

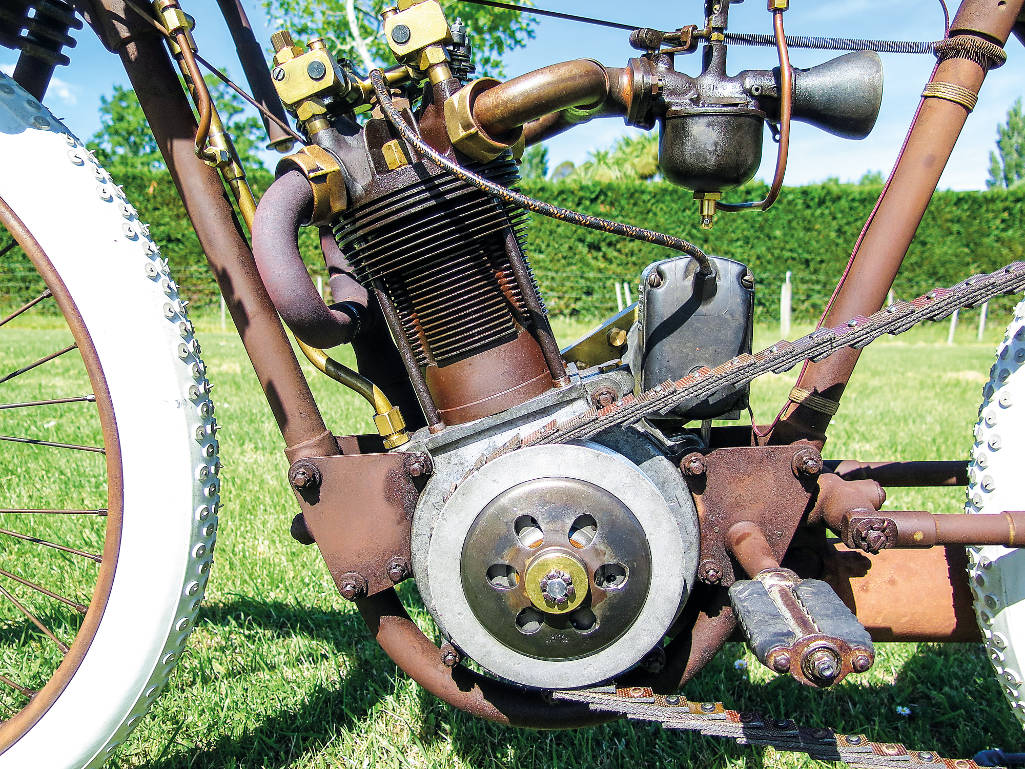

The chain-driven magneto caused no end of difficulties, with the Fairbanks rotary hoe impulse coupling turning backwards, so eventually Chris decided to use a modern GY6 CDI with the battery being concealed under the seat. Typically, a modern bike’s ignition will advance the spark from about 3000rpm, but with the board-tracker not reaching such dizzying levels, a programmable unit is to be tried, with more advance being given just off idle.

The cylinder is a modified VW 1600cc one, and, because of the mounting holes being different between the JAP crankcases, the barrel, and the cylinder head, has been adapted to mount using plates that compensate for this. The connecting rod is Chromoly and has been machined to suit the crank and gudgeon pins. After the engine was test started on the bench, it was found to be very loud and vibratory, but further machining reduced the compression ratio to a manageable 6:1, and it was useable at that.

The cylinder is a modified VW 1600cc one, and, because of the mounting holes being different between the JAP crankcases, the barrel, and the cylinder head, has been adapted to mount using plates that compensate for this. The connecting rod is Chromoly and has been machined to suit the crank and gudgeon pins. After the engine was test started on the bench, it was found to be very loud and vibratory, but further machining reduced the compression ratio to a manageable 6:1, and it was useable at that.

By October, and by using some rusty old 3” rims shod with irrigation tubing, the bike’s frame could be mocked up. Chris replicated early 20th Century construction of cast frame lugs by fabricating, TIG-welding, smoothing and then shot blasting the finished lugs to replicate a casting and the frame tubes were then pinned and brazed into place.

Plates were made to attach at the steering head, and the stem pressed in. As there is no suspension, only the flexing of the tyres gives any comfort. On the left side, the frame is joggled to allow clearance for the drive belt, which has been coloured using polyester clothing dye and acetone. The spoke-mounted pulley is made from hardwood timber from a delivery pallet, with the power being transmitted directly through the spokes to the rim.

Once the wiring was finished, it was time to start the finished machine, but Chris found that using rollers was fraught with danger, given that there are no brakes or a clutch – start the bike and you are away! After some consideration, he decided to fit a centrifugal clutch behind the engine pulley, so that the bike can idle without moving. This meant that a new starting system had to be devised, and is by use of an industrial electrical paint mixer, which has the great advantage of a soft start, taking several seconds to reach full power, and thus removing any sudden loading of the engine.

The starting procedure is to open the exhaust valve lifter on the left hand twist grip, allowing the engine to turn as fast as the mixer can before engaging full compression and adjusting the conventional throttle with the right hand twist grip. Ironically, Chris found that a modern carburettor gave hard starting and poor throttle response, but once an overhauled Ford Model T carb was installed, it starts more readily and idles smoothly.

Chris has deliberately chosen that his bike look like a barn find that has languished for 100 years, so the only paint is on parts that cannot be seen, and the rest of the metallic parts have been chemically treated using diluted swimming-pool chlorine to encourage the rusty finish. The bike was then washed and oiled to prevent further rusting. The weekend after the bike was finished, it was entered in the annual Smash Palace-sponsored bike show in Christchurch, where it won the People’s Choice’ award, and rightly so, in my opinion.

Chris has deliberately chosen that his bike look like a barn find that has languished for 100 years, so the only paint is on parts that cannot be seen, and the rest of the metallic parts have been chemically treated using diluted swimming-pool chlorine to encourage the rusty finish. The bike was then washed and oiled to prevent further rusting. The weekend after the bike was finished, it was entered in the annual Smash Palace-sponsored bike show in Christchurch, where it won the People’s Choice’ award, and rightly so, in my opinion.

As you can see from the photographs of the bike in action, it has been tested on an 800m trotting track. In all fairness, the performance of the ’tracker is modest, but when I rode it, it felt fast enough. The riding position, when crouched, gives you quite the crick in your neck, and despite the large radius of the track’s bends, it was still necessary to back off the throttle to negotiate them safely. It is never going to be a shingle-spitting, sideways sliding, speedway broadsider, but instead it is a tribute to the men and machines who 100 years ago bravely took part in the highly risky art of racing wheel to wheel without brakes.

It is also a tribute to Chris Gordon’s passion for taking an idea and making it work, with the result being, after 1000 hours of work, the splendid bike that you now see.

What was Board track racing?

Board track racing was a popular form of motorsport in the United States during the early 20th Century. Racing was fast, with speeds reaching over 180kmh on the circular, often kilometres long tracks. The tracks themselves were constructed from wooden boards (whereby the sport’s name came from), due to it being initially cheaper to construct a track from wood rather than ashfelt or concrete. But, due to the high costs of maintaining the wooden boards most tracks had a shelf life of less than five years.

Board track racing died out in the 1930s with the onset of the Great Depression one of the main contributors to the sport’s demise.

Specifications:

Bore: 87.0mm

Stroke: 84.6mm

Capacity: 503cc

Piston: Mahle 3-rings

Cylinder Head: Cast iron, 4-valve

Inlet Valves: 30.5mm

Exhaust Valves: 26.5mm, manual decompressor

Spark Plug: NGK CR9E

Wheelbase: 1325 +/- 7mm

Steering angle: 23 degrees

Trail: 94mm

Weight distribution: Front 43kg, rear 45kg