Euro Emissions Explained

While we pride ourselves on our “clean and green” country, the stringent European emissions rules for the vehicles we drive are important to understand for their impact on what we ride.

Words: BRM Pics: Supplied

You’ll often read in these very pages about a bike conforming to Euro 4 – the current crop of regulations bikes need to meet if they are to be sold in EU nations – but why do we bother to include such info, when it has very little obvious impact on the bikes we ride?

Well, the truth of the matter is Euro 4 – and the even tougher Euro 5, due to take effect from 2020 – has a great deal of impact upon the bikes we ride, thanks to the incredibly interlinked world we live in and a little thing called globalisation.

The Beginnings

Euro Emissions aren’t a 21st Century creation, and in fact have been around for longer than many of us realise, with the first crop of Euro emissions regulations coming into effect way back in 1970!

Euro Emissions aren’t a 21st Century creation, and in fact have been around for longer than many of us realise, with the first crop of Euro emissions regulations coming into effect way back in 1970!

It took a while for the regulators to turn their eyes to two and three wheelers, but the powers-that-be eventually decided bikes were putting out too many pollutants in 1997 when Euro 1 was laid down for a 1999 implementation.

To be fair, the motorcycle industry had it a great deal easier than the rest of the automotive world.

Clearly, bikes didn’t pong as much as say, a London taxi, nor were bikes as numerous – even speaking in global terms – so the natural progression to Euro 2 actually took a little while, with 2005 manufactured models being the first in the firing line.

This gave bike manufacturers a bit of breathing space for a good few years to clean up the engines in their machines.

It was the introduction of Euro 3 which dealt a major blow however – with just two years between the Euro 3 and Euro 4, making the 6-year honeymoon period between Euro 1 and Euro 2 seem like an eternity by comparison.

Euro 4 effects

When Euro 4 came into full force on the 1st of January this year – one year after first coming into effect with new MY16 models – the manufacturers didn’t actually have huge problems as far as the emissions were concerned. It was the ‘other things’ Euro 4 called for that were to provide more headaches.

Most of us think of emission regulations when terms like Euro 4 enter into a conversation, but in fact, the emissions are only part of the picture – and an element which can be taken care of reasonably painlessly, as combustion efficiency to enhance performance improves.

The major impact outside of the usual tighter emissions regulations, however, was that every new motorcycle over 125cc sold in Europe required ABS braking, on-board diagnostics, and also had to meet evaporative fuel emissions tests, alongside the exhaust gas emissions tests.

ABS braking system adoption is not as dramatic a problem as it had once had been for the motorcycle industry. BMW should be thanked for making ABS a ‘bearable’ expense for most manufacturers.

When the German brand produced ABS bikes for the first time 28 years ago, the system weighed in at around 13kg. Second generation units came in at 5kgs and today’s ABS systems are barely felt, at under a kilo in weight.

The ABS ‘weight reduction diet’ is presumed to have applied to the development costs, which

has enabled many other brands to go down the same road as the German brand, suggesting the greatest pain to the pocket has effectively been absorbed – thank you, BMW.

However, can the motorcycle industry as a whole, expect some other ‘white knight’ to sort out the mysteries of on-board diagnostics?

Unlike ABS, which pretty much operates on the same platform from one manufacturer to the next, OBD systems tend to be much more proprietary in terms of development and implementation. Or at least – they were.

For the conspiracy theorists who thought OBD systems were designed to ensure factory-trained techs are the only people who should work on engines, some clever bar stewards worked out that if the bikes were going to be so specific, why not find an electronic thing that everyone has as a personal device and turn it into an OBD scanner?

Enter the Smartphone app.

There are a number of these in the market, designed to give the power of engine tuning and maintenance back to the people, especially the people who buy different breeds of bikes, all of which have to conform to a Euro 4/5 OBD requirement.

The Smartphone app (whichever one suits your weapon of choice) means that backyard mechanics who love to tinker still can, even if they have a late model machine equipped with all that new-fangled EFi witchcraft, which sounded the death-knell for carburettors back in days when Bon Jovi were performing with big hair and Don Johnson was cool.

OBD-2 for 2020 might make life a little more interesting, given that motorcycle manufacturers have only just come to terms with OBD-1 and consolidation is still a consideration when it comes to who can see or work on what.

However, the era of the App will mean a minimum amount of manufacturer research that would have had to happen otherwise.

Benefit to the Smartphone-wielding owner of the ODB-equipped bike of course, is greater engine life expectancy. The App can help the home mechanic peak and tweak, but also alerts said mechanic to the time when they should down tools and call on an expert.

And this brings us on to what most of us understand Euro 1 through 4 to mean – emissions.

The Bad Stuff

Euro 4 – where 2017 bikes need to sit – requires significant decreases in carbon monoxide (CO), Hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides (NOx), which have steadily been drawn down since Euro 1. Euro 5 will see these emissions drop still further.

Euro 4 – where 2017 bikes need to sit – requires significant decreases in carbon monoxide (CO), Hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides (NOx), which have steadily been drawn down since Euro 1. Euro 5 will see these emissions drop still further.

The newly reduced emissions are not insubstantial and there are many ways for motorcycle manufacturers to comply. One way is to increase the engine displacement slightly, allowing ‘softer tuning’ without a too-perceptible drop in power.

This mid-sized bike (for the most part) solution will see some popular bikes fall to the history books however – and some manufacturers are finding this a bitter pill to swallow, given the marketable success of some of those machines.

While relatively affordable, upping the displacement only works properly on the CO and NOx counts. Hydrocarbons however, create a headache which is more problematic – and therefore have the potential to impact on dollars too.

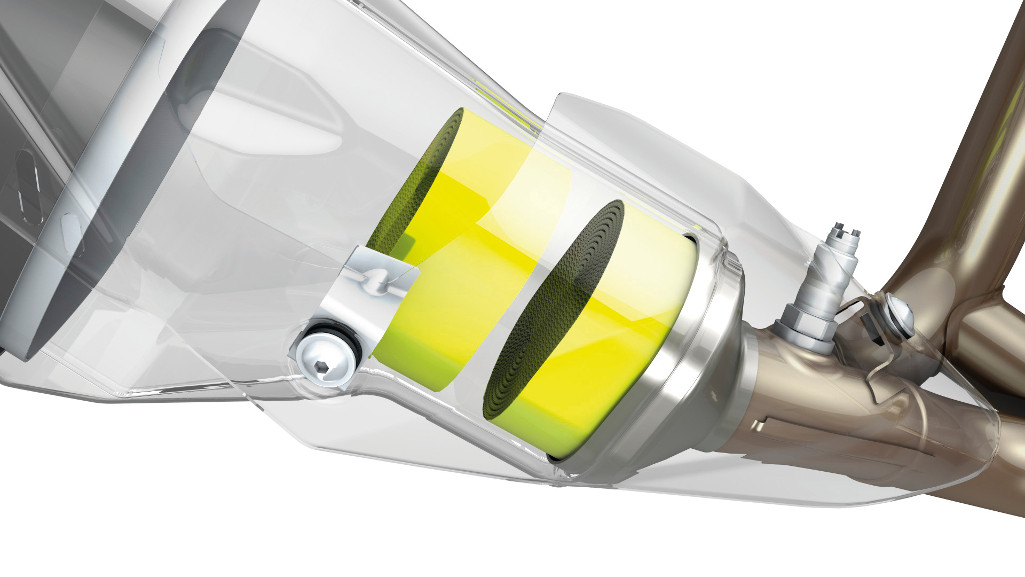

The simple reduction of Euro 3 hydrocarbon allowance of 03.0 g/km to Euro 4’s 0.17g/km may not sound like much, but when you are looking at meeting it by increasing the size of a catalytic convertor, the problem becomes serious.

The catalytic convertor is a major factor in emissions control. It handles NOx reduction and CO minimisation, but it also goes a long way to taking care of hydrocarbons.

‘Cats however, are not cheap, requiring exotic metals to do their thing – specifically, platinum, palladium and rhodium to dispel the respective nasties. Thus, the bigger the ‘cat, the pricier it becomes by virtue of the exotic metals.

And if you thought that was the end of the ‘cat problem for manufacturers, think again. There’s design and build issues to consider.

A big ‘cat takes up a big amount of space and already, we have started to see fall out from prospective buyers of 2016 bikes who have termed some machines ‘hideous’ as a result of Euro 4-compliant design considerations and taken their chequebooks elsewhere.

But wait – there’s more.

To comply with Euro 4, the bike’s emissions are considered when the bike is standing still too.

Fuel vapour – and this why you shouldn’t sniff petrol, kids – has a higher proportion of unburned hydrocarbons than exhaust fumes, which means your bike, sitting innocently in your garage is quietly farting out hydrocarbons through the breather hose.

How much, is something which has the Euro police concerned. To find out, a Euro 4 compliant bike must be put through a SHED test.

The acronym is particularly amusing, SHED standing for Sealed Housing for Evaporative Determination so, literally putting the bike IN a shed to do a SHED test!

Actually, the ‘shed’ is a container equipped with sophisticated sniffers to see just how flatulent your bike is when at rest, engine off and doing no harm to no one – or thus it would seem.

To top it all off, with reduced outputs of CO, NOx and hydrocarbons, Euro 4 insists that the bike not get any worse – emissions-wise – over a predicted period of 20,000km – and inspectors need to see the proof of this, please.

That’s OK, for Euro 5, compliance calls for lifetime emission control – how long is that?

About as long as a piece of string – smelly string.

But we’re not in Europe…

Okay, we may not have been A+ students of Geography back in high school, but even we know that New Zealand is about as far away from Europe as you can get – so why do we give a stuff about Euro Emissions?

Okay, we may not have been A+ students of Geography back in high school, but even we know that New Zealand is about as far away from Europe as you can get – so why do we give a stuff about Euro Emissions?

In a nutshell, we care because the manufacturers care. New Zealand is a small – very small – market, with less than a month’s production run for a big player eclipsing our total market sales volume for a year.

Since manufacturers in most cases don’t make bikes for us specifically (for example: our LAMS bikes are often nearly identical to the European A2 scheme), so we have to take what we’re given.

So, when you see a bike land in the showroom, a huge boil on its butt making up the cat, new digits on the dash, decals on the discs and a gas mask on the breather hose and you think ‘MiGawd that’s ugly,’ please remember that was probably not the way a hapless bike designer envisaged his life’s work. He’s just doing what he had to do.

It’s also worth remembering that Euro emissions are doing their thing when it comes to taking care of the planet. So, we can’t beat them up with the chastisement stick too much either.

All we can do is be mindful that the advancements are just that, designed to make our rides, better, safer and cleaner. Sadly, that may cost a little more, but it is only a little more and the benefits far outweigh the negatives.

Euro 4 doesn’t apply to…

– Vehicles designed for the exclusive use by the handicapped

– Vehicles with a maximum speed under 6km/h

– Vehicles exclusively intended for use in competition

– Self-balancing vehicles

– And finally, vehicles designed and constructed for use by the armed forces, civil defence, fire services, and forces responsible for maintaining public order and emergency medical services

Euro Emissions regulations through the years

| EURO 1 | EURO 2 | EURO 3 | EURO 4 | EURO 5 | |

| YEAR | 1999 | 2005 | 2007 | 2016 | 2020 |

| CO | 13.0g/km | 5.5g/km | 2.0g/km | 1.14g/km | 1.00g/km |

| Hydrocarbons | 3.0g/km | 1.0g/km | 0.3g/km | 0.17g/km | 0.10g/km |

| NOx | 0.3g/km | 0.3g/km | 0.15g/km | 0.09g/km | 0.06g/km |

| SHED test | n/a | n/a | n/a | yes | Yes |

| Onboard Diagnostics | no | no | no | Yes (OBD1) | Yes (OBD2) |

| Durability Test | n/a | n/a | n/a | 20,000km | Lifetime |