Tucked away in the shadow of the Bay of Plenty’s Kaimai Ranges is a manshed many bike riding enthusiasts would be happy to escape to. Looking like nothing out of the ordinary, what’s inside is far from it.

Words & pics: Fraser Davey

Said shed belongs to 50-year-old painter and engineer, Keith Edwards, and contains no less than thirty examples of Honda’s XR range in various states of repair and restoration. Born and bred in Te Aroha, then growing up at Waihi Beach, Keith, like many motorcyclists, caught the bike bug at an early age after a ride on his cousin’s 1984 XR80 when he was around eight or nine years old. His fascination with working on bikes started not long after. “My stepdad had two Honda XL250S’s in the shed, which he let me tinker with, which was probably got me into it. I thought they were cool”, he says.

Looking around Keith’s workshop at the restored bikes and the various parts ready to be reinstated, it’s easy to see the level of detail and quality of finish on his bikes – they’re pretty much factory spec. “I’ve always been fussy,” says Keith, “that’s my biggest fault. My dad used to get really annoyed with that side of me. With my first 600, I used to take it home at weekends and pull it down and clean it right to mint and paint up all the nuts and bolts. I just loved it and having that nice bike.”

A 1984 Honda XR200 was Keith’s first bike, which he bought at age 16 after riding pillion around Thompson’s Track (a popular riding spot for many years around the Bay area) on his mate Derek’s XR200. “It was pretty full-on, but I really enjoyed it. By the time I bought my 200, there were five of us who had them, 200s and 250s of that REera, so we all used to burn around Waihi on XRs. From there I progressed into the later 250s, then 600s. I was the first one of us to get a 600, which I bought from my uncle’s mate. Consequently, I did over 160,000km on that bike.”

After owning various incarnations of the dual-purpose machines, Keith progressed into riding road bikes, of course, all Hondas, including an XRV750 Africa Twin (“A cool bike, but I lost a lot of money when I traded it on a new XR400”), a VFR750, CBR1000 and finally one of Honda’s fastest street bikes, a Blackbird. “I got my 300km/h plus on that, which was cool, then got back into the XRs because they’re just so versatile, and you can go and do stuff that you can’t do on the Blackbird.”

A return to XR ownership kicked the restoration bug up a gear. With both his dad and stepdad being mechanics and helping with engine work, and buying and reading lots of owners’ manuals, Keith’s knowledge on XRs was becoming extensive. In 2004 he undertook his first real full restoration project. “The bike was a ’88 250 that had been broken into bits, and I just started on that, and from there, it just progressed slowly to what it is now,“ he says. Since then, he has worked on between eighty to a hundred XRs. Excluding his own bikes, he is currently restoring four bikes belonging to other people, all 500s from ‘79 to ’84.

Spending upwards of 30 hours a week on his “hobby”, Keith hopes to transition this obsession into a full-time business, where his biggest potential client base would be overseas, namely, Europe, Australia and America, who, according to Keith, are huge on XRs. “Through this little journey, we’ve met so many people from around the world; it’s been cool. We’ve got an air crash investigator in the States who would like us to build him a bike. He said if I ever wanted to sell one of mine, he’d buy it, but if I could do one for him, we’ll have a look at it.”

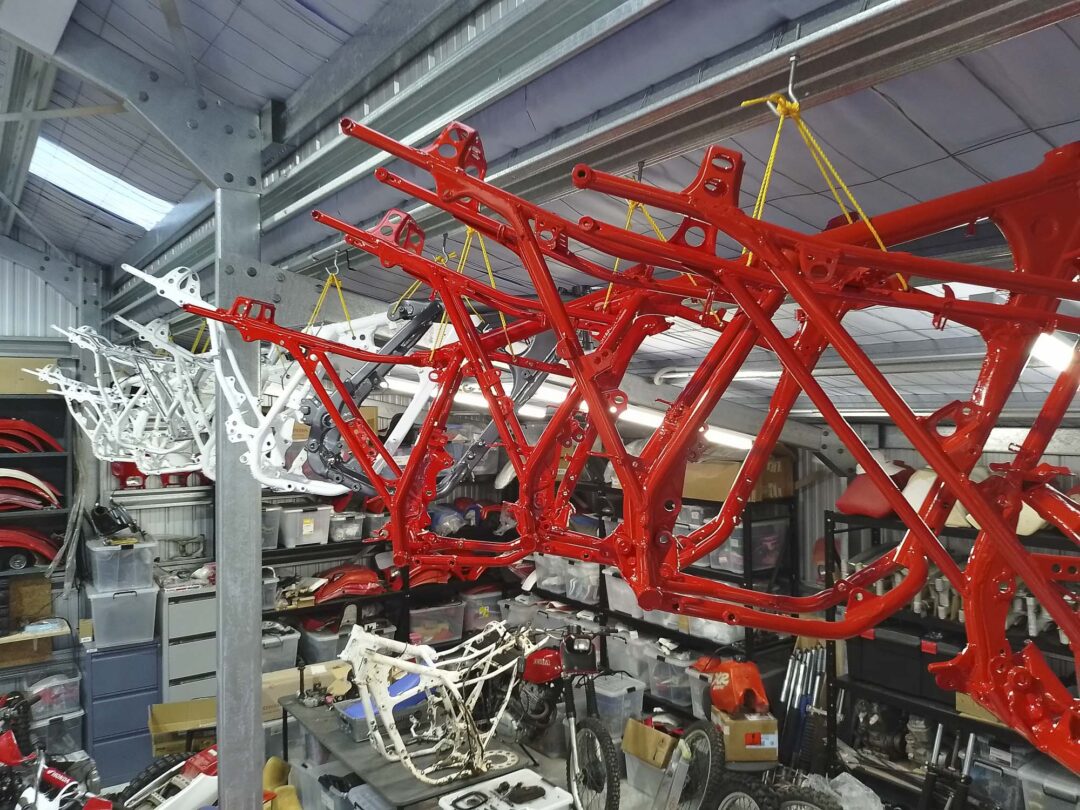

Keith is basically stripping all his bikes completely and rebuilding them from scratch, so he’s well up to play with the most common faults or issues that need to be remedied or improved upon, which, unsurprisingly, he says, are the frames. “New Zealanders using them for farming and treating them like shit, the frames basically just rot away, so I replace and rebuild frames, “he says. “I’ve got a few 400 frames on the go now. If I’m doing one of my own, I coat the inside (of the frame), and if people want to do it, I will fill them completely with an epoxy, so they’re solid. It’s solid rust kill and gives that strength, too.”

However, the most challenging part of many restorations, according to Keith, is the plastics. “Pricks of things,‘ he says. “They are rare to find with good plastics; they’re usually faded and old and a bit scratched up, and there’s a significant amount of work involved in bringing them back to new. Some it’s just polishing, but others get a paint job using flexible paint. When I’m finished, you really can’t tell. The painting really is my forte and that’s what makes the finish original. All the colours are colour-matched; you’ve got to make them look right. “

Sourcing parts for bikes that, in some cases, are over forty years old is no easy task, but over the years, Keith has established contacts in Japan, Australia and, surprisingly, Portugal, where apparently his man has a plethora of parts. Due to the increasing rarity of original parts, prices are now bordering on ridiculous. The XR500, according to Keith, is one of the harder models to find parts for, and subsequently, a set of hand-guards will set you back around $1500 per set, and a speedometer can be twice that amount.

With the number of bikes and parts he’s purchased, Keith has spent tens of thousands of dollars and invested thousands of hours of his time, which begs the question, what does he plan on doing with all his bikes? “Bring them to as original as I can, then sit on them,” is the reply. “It’s an investment. I did sell one, my ‘89 600. My wife thought I could never sell one, so I did, to sort of prove to her that I could, and I wish I hadn’t because it was such a cool bike.” Keith sold the bike for $7500 in 2018, and he spotted it on Trademe recently for $25,000.

With values of bikes and parts soaring to record levels, it seems Keith’s investment will definitely pay dividends. That said, it’s more likely that the enjoyment he gets from bringing these bikes back to life is worth way more.